Reflections on Being “Capital L” Lost

The nowhere-ness of my white European settler lineage

Author’s Note: this post is about something that is a work in progress, moving, dynamic, that will surely change as I/we continue to explore it. Please keep this in mind as you absorb this piece and the ways that it lands for you.

I parked my car on a side street a few blocks from my house. I had a call with my therapist and didn’t want our nanny to overhear my vulnerable disclosures from the next room. I could tell that it was going to be a tearful session.

A light rain pittered and pattered on my windshield as I tried to describe to Rachel, my longtime therapist and mentor, the deep, bone-marrow sorrow I was feeling that day. I told her how far from the ground I felt, how I was at once floating above life but also subsumed by its demands. After I spoke for a while, Rachel asked if, in my heart, I felt as if I was living the wrong life.

I thought about this for a moment, running through the various aspects of my life in order to find out where I felt the raw rub. My marriage? No. Parenthood? No. Work? No. I closed my eyes and felt a soft truth bubble up. I realized that I feel as if I’m living in the wrong time in history, the wrong culture, and in the wrong place.

For years, my awareness of how civilizations have developed and what it’s done to our bodies and our connection to the earth has been building. I understand now that when humans devoted themselves to agriculture, a profound shift in our psyches and relationship to the land occurred. This was the origin story for private property, war, patriarchy, capitalism, and most of the other ills whose cumulative effects are now reaching a crescendo. Generation by generation, field after field of grain, my ancestors lost - by force or voluntarily - their relationship to the magic and mystery of goddess traditions and their embodiment of the earth’s rhythms. They would have experienced the bloody birth of capitalism - forcible removal from communal lands, wage labor, and the gruesome witch hunts.

My last European ancestors, who dwelt in the wet, fertile areas of present-day Germany, Wales, and Ireland, would have had the old ways living in their bones even if their predecessors had converted to Christianity. They would have walked on lands that had recycled the physical matter of their buried dead - lands that would have recognized their gait, their language, their stories. In famished desperation (or maybe because it was their destiny), in the late 1700s and early 1800s, they gave up more than they knew and boarded boats for the so-called “New World.”

In this unfamiliar place, they became initiated into whiteness and moved farther and farther away from the medicinal, life-giving wisdom of their ancestral lands. As illuminated to me by Resmaa Menakem in his book My Grandmother’s Hands, centuries of violence and trauma living in their white bodies was compounded as they inflicted more of it on to others with black and brown bodies. Swept up in the elusive promise of better, more comfortable lives, I imagine them plowing the dirt and becoming busier and busier so as not to hear the screaming pain that had followed them across the Atlantic. Traumatized, propagating trauma, and now cut off from the spirits of the land that used to hold them, many of them embraced the myth of progress and its soothing promise that everything was getting better.

And so there I was, embodied but ungrounded, carrying the unanswered pain of those old ones, crying to my therapist through the headphones connected to my iPhone.

“I feel completely Lost,” I told her. “Capital “L” Lost.”

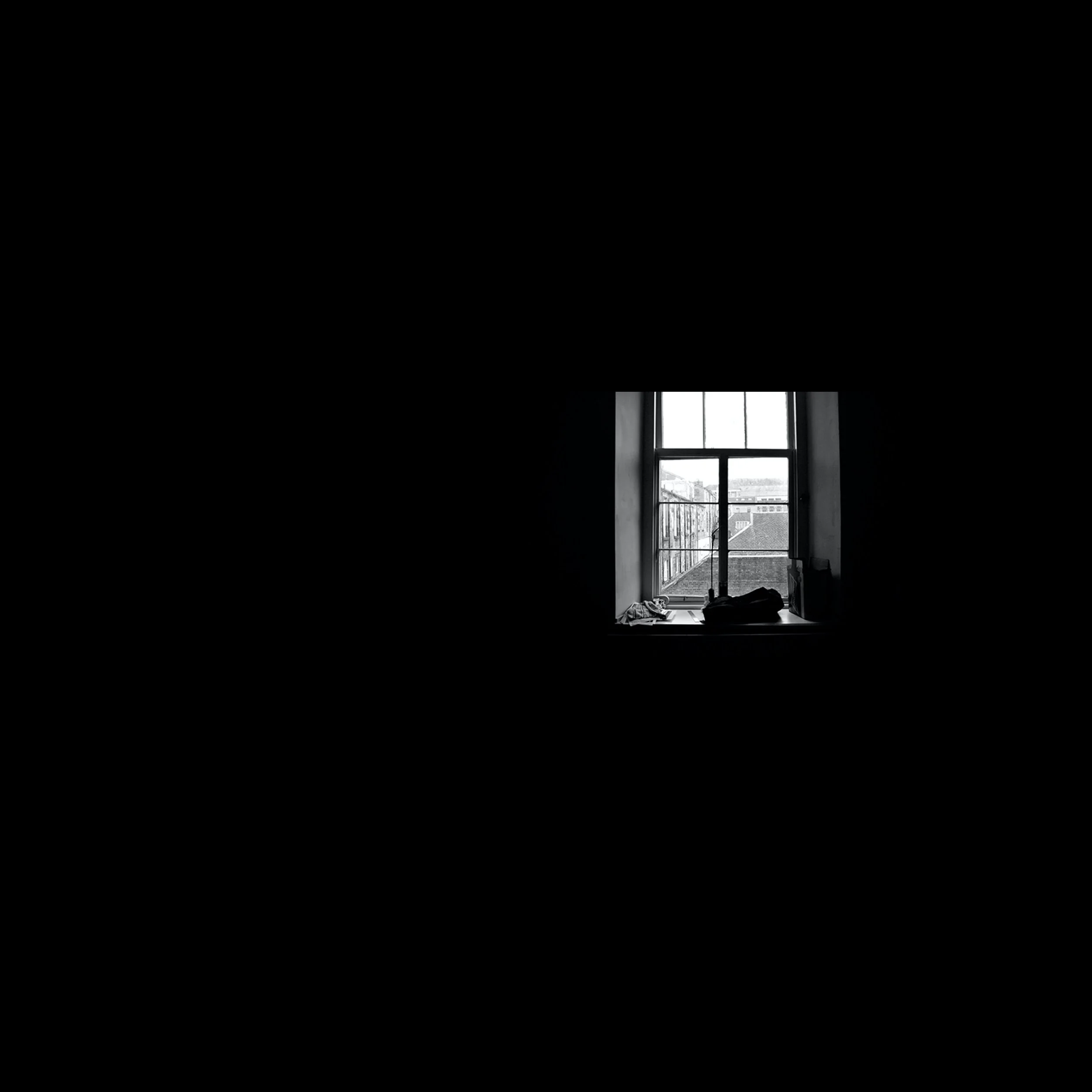

Photo by Josh Nuttall

I am untethered, indigenous to nowhere, given no guide except for the holographic lies of white supremacy and capitalism. While no land can be possessed or owned, I do believe that it can be known, and the land that I inhabit today is so unknown by me. This is not land that yearns for me or that my ancestors would have sang over as they harvested the roots and berries that sustained them. None of my kin are buried in this dirt, none of the old plant names grace my tongue. My hikes, forest baths, and bird-watching feed me, but there is always a distance, like I can’t quite merge with the music of this place. It is as if I’m never home.

Humans have always migrated, of course. Refugees the world over honor and feel their heritage no matter the land they live on. But civilization and capitalism come at a great cost; like Silvia Federici notes in so much of her work, the tearing apart and chipping away of the ties within a community (including the ties to land) are necessary for these two great behemoths to exist. If we are all constantly moving in order to follow work, or if wars between states and climate chaos force us to disperse in desperation, what resistance can we cultivate? We are not stationary plants rooted in place, but we are also not migratory birds. We have these heavy bodies that desire to be close to the ground, mobile but not constantly in flight. We are moving so often that not only do we forget the lands of our forebears, we also forget the land that we skim over or inhabit in brief periods, not even staying from one generation to the next.

When I hear the words of Native writers and poets who describe the impossibility of separating the land from their identity, something in me flutters awake. I have never been to Ireland, Germany, Wales, or the other parts of Western Europe and Scandinavia where the last of my native ancestors lived. It’s possible I would go there and feel nothing; there is, after all, capitalism and concrete all over the world now. But when my mother went to the land where her father’s family was from in Ireland, she told me she wept. She felt something. And not just an intellectualization of heritage, but - I hope - an echo in the double helixes of her DNA. It makes me wonder what could be unlocked, healed, understood if I could place my body in the parts of this world where my wise relations once lived.

Until then, I am here, in this place for no apparent reason and without any true connection. I am a true “scatterling,” as Martin Shaw describes in his book, Scatterlings: Getting Claimed in the Age of Amnesia. He defines a scatterling as “One who has no fixed habitation or residence.” I feel this wandering, meandering tune in my body, but not in the ancient ways of nomads or hunter-gatherers. I feel it as abandonment, as a casting-out, as a nowhere-ness. I feel it as rage at all of my ancestors who gave up their wisdom for the cheap thrills of comfort and convenience. I feel it as sorrow for the fact that they had to.

Photo by Carl Newton

Will I always be a scatterling, surrounded by so many other scatterlings? Is it the destiny of all those who are driven from their homelands or whose ancestors made choices that their descendants have now come to resent? My sense is that this is particularly true for those of us in white bodies, whose European ancestors helped birth and were birthed by capitalism and its ghostly hollowness. After all, despite the fact that the forced resettlement of indigenous peoples in the so-called “United States” was unspeakably gruesome and unjust, with long-standing consequences across generations, many tribal peoples have still retained pieces of their culture and their connection to something older than the tropes of capitalism. I have yet to find descendants of white Europeans who are collectively holding onto - and living out - an indigenous way of being that comes from their own heritage.

One path is to say that I can make this land my home - that with enough effort and offerings, I will know and be known by it. Perhaps it could claim me. I half-heartedly walk this path, racked with doubts about the likelihood that I can grow deep, interconnected, culture-making roots in a place just because I decide to. I impotently look into the local watersheds and topography or do some research on a local bird occasionally, trying to will myself to be in relationship to this place, but there is a block within me that feels large and insurmountable.

Another path, which I am also on, is to call out to my ancestors from across time and space and attempt to understand where the pain started, how it can heal, and where I’m meant to take our family line now. Is it back to the ancestral lands of my forebears across the Atlantic? What would it mean to make a conscious return back to the water, soil, and rocks that hosted my forebears over 200 years ago? How long is the land’s memory? I am wondering what it would mean to make a return to the old lands, the old spirits, the old ways. To envision this feels as thrilling as it does preposterous.

Mostly, I am not walking on any path, but am metabolizing innumerable questions. Am I meant to find solace in the woods here, doing my best to relate to this place where the ancestors of the Chinook, Clackamas, and Multnomah tribes once walked? Is it possible for a descendant of settlers to become intimate with the very land that they colonized and abused? Am I meant to stay here, in what is now called Portland, facing the consequences of 10,000 years of post-agriculture pain alone in my home with my small nuclear family? Is there any clarity or solidity I can leave my children so that they are not also Lost?

I don’t know much yet, but I am asking these questions. At times the idea of searching for and receiving an answer to any of them feels like more than I can expect to do in one lifetime. And yet, I find some boldness in the idea that if I’m already a scatterling, with no home or covenants made, I have nothing else to lose.